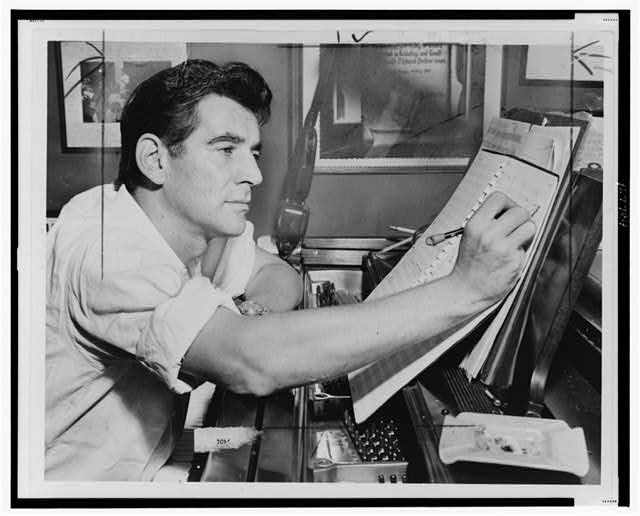

I interviewed cartoonist Charles Burns (Black Hole) about his new graphic novel Final Cut and the creative block that led up to it for Publishers Weekly:

Whenever he tried to start a new project, it fizzled out. “I went for months and years,” Burns, 68, says via phone from Philadelphia. “This is shit,” he remembers saying to himself. “I should know how to do this.” Facing what he calls the worst creative frustration of his career, he found himself thinking, “Maybe this is it. Maybe I don’t have anything at all.”

So, to prove he still had something in the tank, Burns set himself a small goal: finishing a seven-page story. If he couldn’t do that, he told himself, he’d have to start doing something else…

Final Cut comes out in September.

You must be logged in to post a comment.