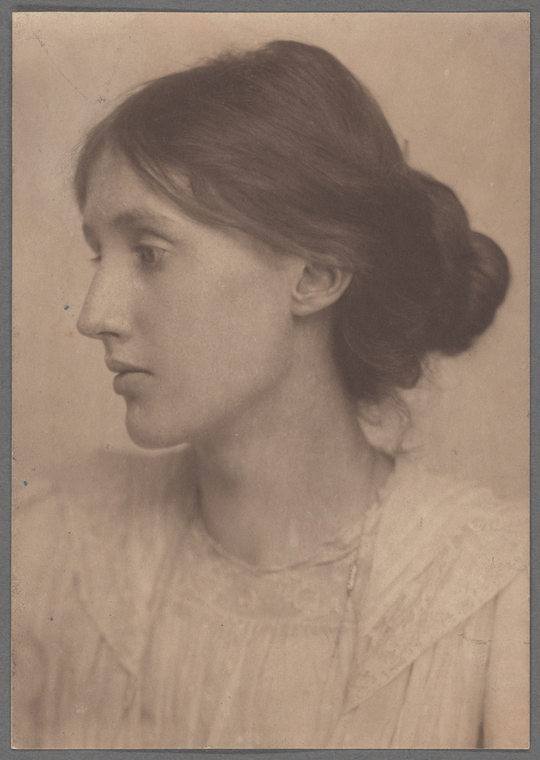

One of Virginia Woolf’s more famous essays is “How Should One Read a Book?” And rightly so. It’s a loving and vigorous defense of not just reading itself but how to approach it with both a judicious and wide-roaming eye. She insists, in short, on reading whatever you please:

To admit authorities, however heavily furred and gowned, into our libraries and let them tell us how to read, what to read, what value to place upon what we read, is to destroy the spirit of freedom which is the breath of those sanctuaries. Everywhere else we may be bound by laws and conventions—there we have none…

Use the same approach when writing. Hear people out, seek their counsel, take what makes sense. As Woolf says about reading:

The only advice, indeed, that one person can give another about reading is to take no advice, to follow your own instincts, to use your own reason, to come to your own conclusions…

Write freely, but not thoughtlessly.

You must be logged in to post a comment.