Everybody expects writers to be, for the most part, miserable. This is particularly true of writers themselves. We are after all a cohort of people given not only to romanticizing what we do but at the same time highlighting just how difficult a task it is to write sentences one after the other.

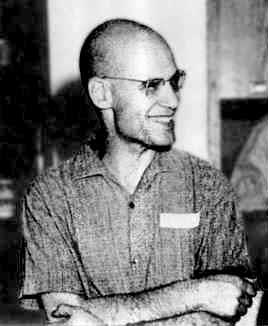

Michael Cunningham (The Hours) wrote a piece for Oprah about this predilection:

I suspect that one of the many reasons we who write tend to contemplate our troubles the way nuns finger rosaries is the fact that our sufferings are entirely invisible to everyone but us…

But while Cunningham was gently ribbing his tribe of creatives and pointing out that sometimes the act of writing can be quite enjoyable (“If an author isn’t acquainted with happiness in some form or other we don’t trust him or her”), he also pointed out that whenever the writing went a little too well, that is when the writer is in trouble:

A writer should always feel like he’s in over his head. That’s part of what makes good writing compelling—the sense that as readers we’re in the company of a writer of vast ambitions, who is always trying to do more than he or she is technically capable of…

Do you have a project that you would love to write but have been putting off because you think it’s too much for you or you don’t have the skill? Make that the next thing you write.

You must be logged in to post a comment.