For obvious reasons, we read writers about writing because, well, who else are you going to ask? We like to look to those we love, and maybe occasionally to those who we may not love so much but because we think: Damn, look at how he’s done, how did he do that?

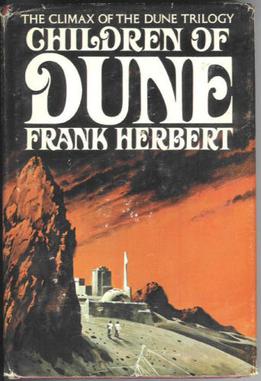

Which brings us to Frank Herbert. There are people who love just about everything he’s written and others who think that the Dune series, well, it fell off a bit after the first two. Nevertheless, given what he accomplished with the first Dune at least, many people listen to what he has to say. Like when he says this:

A writer’s job is to do whatever is necessary to make the reader want to read the next line. That’s what you’re supposed to be thinking about when you’re writing a story. Don’t think about money, don’t think about success; concentrate on the story—don’t waste your energy on anything else. That all takes care of itself, if you’ve done your job as a writer. If you haven’t done that, nothing helps…

I know what he is trying to say here. And it needs to be said. No matter what else you do and no matter how many rules you follow about exposure and making connections and studying the market and all that, none of it will mean anything if you haven’t put everything you’ve got into the work itself.

But still, telling writers, especially new writers, that nothing else matters? This feels like malpractice. Of course, the story is everything. How about the working parent who can only get an hour or so of solid writing time in between shifts and the baby? Doesn’t it make sense for them to consider focusing on what they can get done in that time and that headspace rather than putting hours and hours into a thing they may never be able to finish?

Of course the story is everything.

But money is not nothing. Neither is life.

You must be logged in to post a comment.