Say you have written a book. You have been lucky enough to have your book published by a major house. Maybe you have even gotten some good press. But nevertheless, the income stream is negligible. What do you do to keep writing and not have to hold down a separate job?

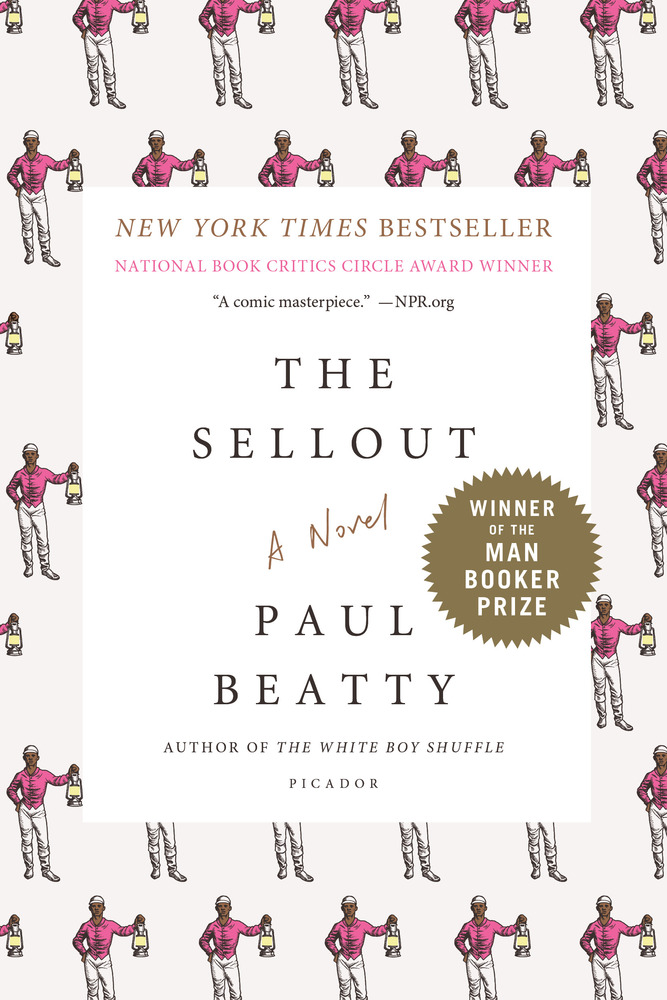

Maybe write a book that has a better chance of being optioned for a streaming or television adaptation. In “The Rise of Must-Read TV,” Alexander Manshel, Laura B. McGrath, and J. D. Porter note how streaming services like Netflix (which has had great success with book-sourced series like The Queen’s Gambit [pictured above]) have been on a “buying spree” of book properties.

The writers studied what makes a book more appealing to the interests of TV producers looking to populate a big, broad-appeal series. They identified a few common characteristics:

Although not every novel under contract for potential adaptation shares all of these features, they do seem to possess a consistent set of what we call “option aesthetics”: episodic plots, ensemble casts, and intricate world-building. These are the characteristics of contemporary fiction that invite a move from the printed page to the viewing queue.

These are just dramatic choices you can make. If (and only if) they work well for the story you have in mind, then run with it. Remember: Jennifer Egan modeled A Visit from the Goon Squad on The Sopranos.

You must be logged in to post a comment.