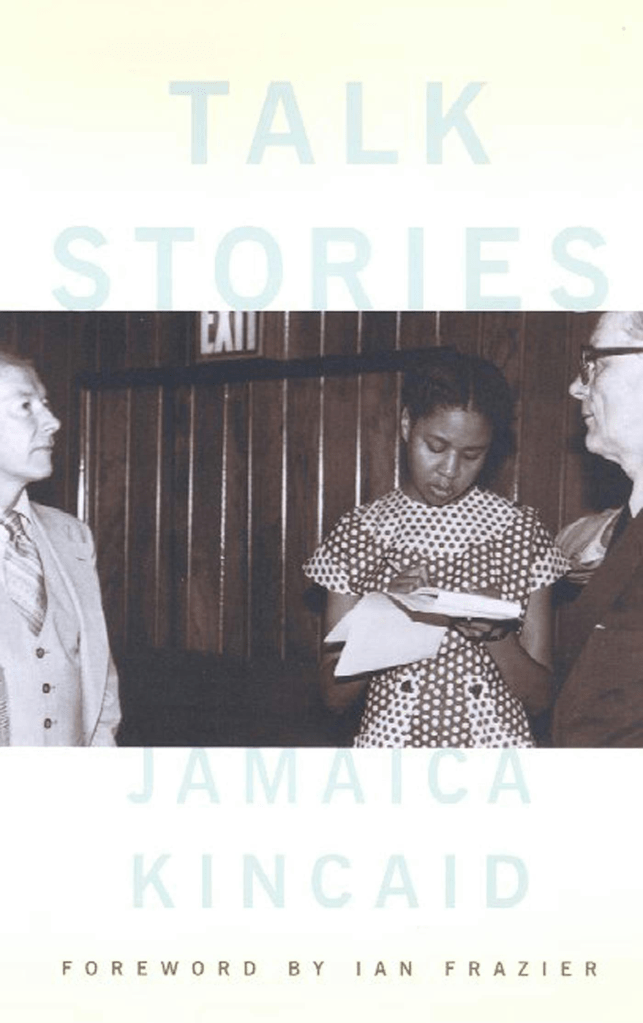

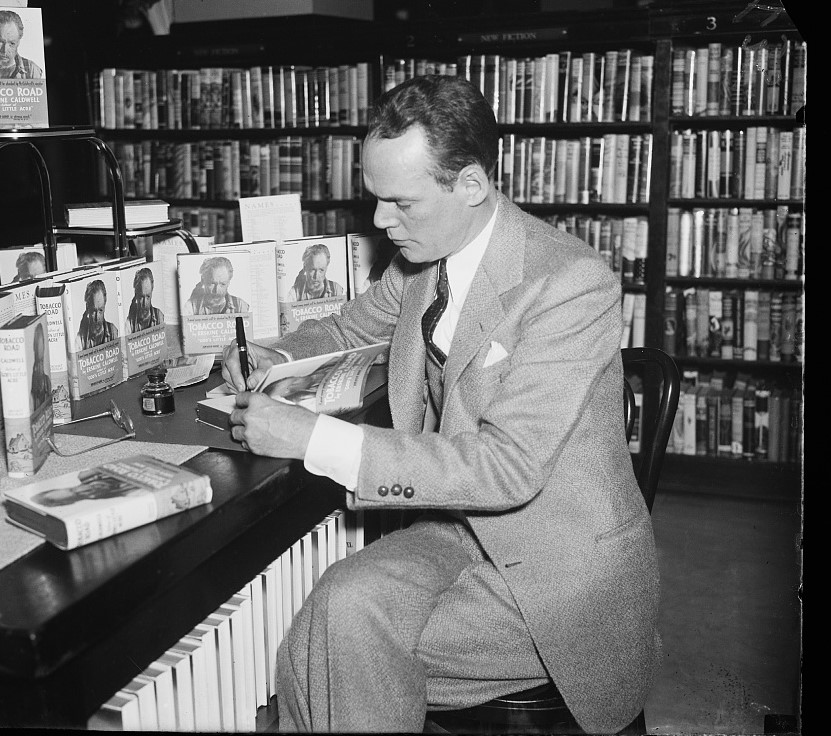

In an interview with Guernica, Jamaica Kincaid dismissed the idea that writing is a real profession, no matter how much people try to make it into a career:

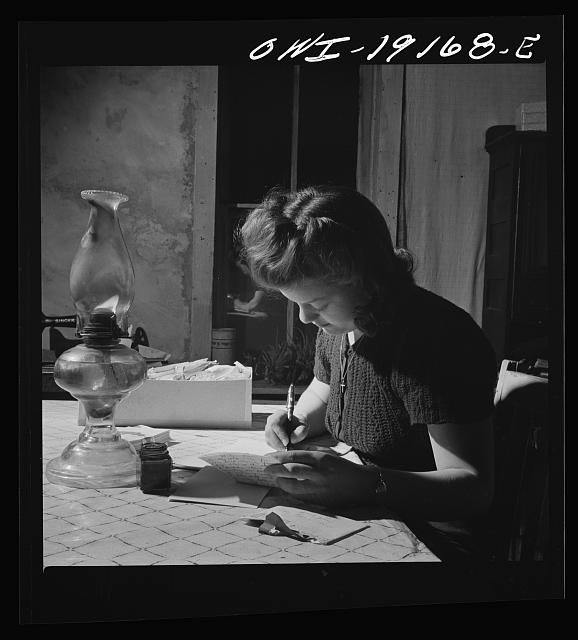

The thing about writing in America—and I just recently understood this—is that writers in America have an arc. You enter writing as a career, you expect to be successful, and really it’s the wrong thing. It’s not a profession. A professional writer is a joke. You write because you can’t do anything else, and then you have another job. I’m always telling my students go to law school or become a doctor, do something, and then write. First of all you should have something to write about, and you only have something to write about if you do something. If you just sit there, and you’re a writer, you’re bound to write crap. A lot of American writing is crap. And a lot of American writers are professionals. Writing is not a profession. It’s a calling. It’s almost holy…

You must be logged in to post a comment.