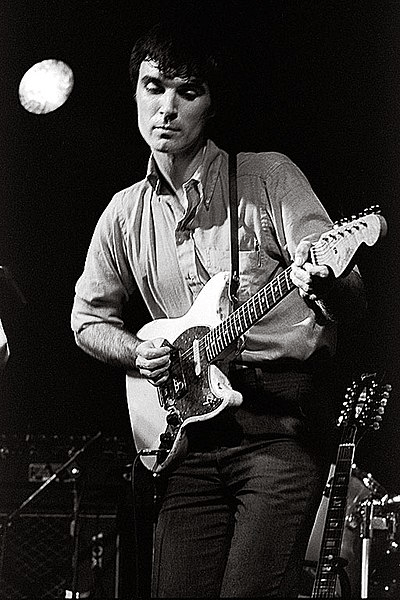

Before becoming the kind of writer who can get published anywhere from Tin House and Granta to the Wall Street Journal, Phil Klay spent several years in the Marine Corps and was deployed to Iraq. He drew on that experience to create his National Book Award-winning classic, Redeployment.

A hell of a writer who can deliver both piercing insight and gut-wrenching emotion on the same page, Klay would seem to produce his work from a place of superior confidence. But as he related in this interview, not so much:

Putting the story on the page is a product of doubt, not a product of certainty. I write because I’m troubled or confused or fascinated by something in human experience I don’t understand, and writing allows me a way to expose my own ignorance further. For me, a story begins with questions far more often than with answers. And even if I do have some very fixed notions at the outset of the story, writing usually complicates those notions or destroys them altogether…

See your uncertainty as a clue of where to start and a sign of something worth exploring, rather than a topic to be avoided. It’s like one of General Mark Milley’s favorite sayings, “Move to the sound of the guns.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.