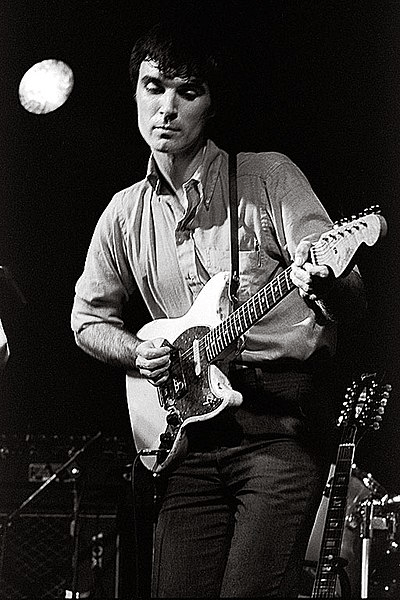

Like a lot of celebrities, David Byrne has given a commencement address. Unlike a lot of celebrities, he had a lot to say beyond empty “you can do it!” exhortations.

Per Rachel Arons, Byrne’s 2013 address to the graduating class of the Columbia University School of the Arts was in many ways, a downer. He referenced something that actor and theatre director Paul Lazar once told him:

‘You know, there’s no guarantee of making a good living, moneywise, in [the art] world, so if that’s what you want—you know, monetary success, if that’s where the value lies—maybe you made a wrong choice quite a few years ago…

All true. Most people in the creative field—whether music, writing, art, or making gigantic papier-mâché puppets—will not and should never expect to make a good or even sustainable living through that alone.

But while delivering this cold-water splash of reality, Byrne did not aim to turn people off from the arts, merely to let them know how to adjust their expectations:

I believe that there is a way to have a very, very satisfying, enriching and creative life in the arts, but it depends on what criteria you use to look at that. But I would say that if you’re being creative, with happiness, satisfaction, all that—you’re succeeding…

Yes, an audience is preferred, as well as high amounts of remuneration. But sometimes, good work alone is all the necessary reward.

It’s more than most people can expect in this life.

You must be logged in to post a comment.