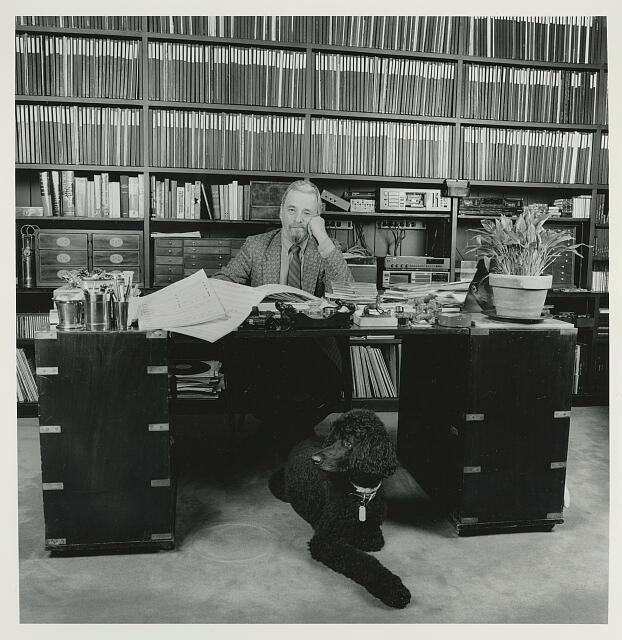

In his enthralling new biography on William F. Buckley, Sam Tanenhaus says the following about his subject’s approach to his work:

Like so many writers he loathed the act of writing, but like very few he did it with speed and efficiency…

Buckley spent a career making use of that efficiency. For many years, he wrote multiple columns a week while editing the National Review, hosting Firing Line, and publishing dozens of books (sure, some were padded collections of columns and letters, but still), not to mention swanning around high society affairs, going yachting, and generally engaging in the life of a gentleman. He accomplished this through efficiency. Not messing around. Knowing what he wanted to say before firing up the word processor.

In 1986, Buckley took to the pages of the New York Times to make an argument for fast writing. A scold over at Newsweek had snarked that Buckley sometimes spent a mere 20 minutes on his newspaper columns, which was apparently too little time for serious writing. Buckley responded in indignation:

It is axiomatic, in cognitive science, that there is no necessary correlation between profundity of thought and length of time spent on thought … I am, I fully grant, a phenomenon, but not because of any speed in composition. I asked myself the other day, Who else, on so many issues, has been so right so much of the time? I couldn’t think of anyone. And I devoted to the exercise 20 minutes…

See what you can get done in that much time. Hold yourself to 20 minutes. Then do it again the next day. And the next.

You might be surprised.

You must be logged in to post a comment.