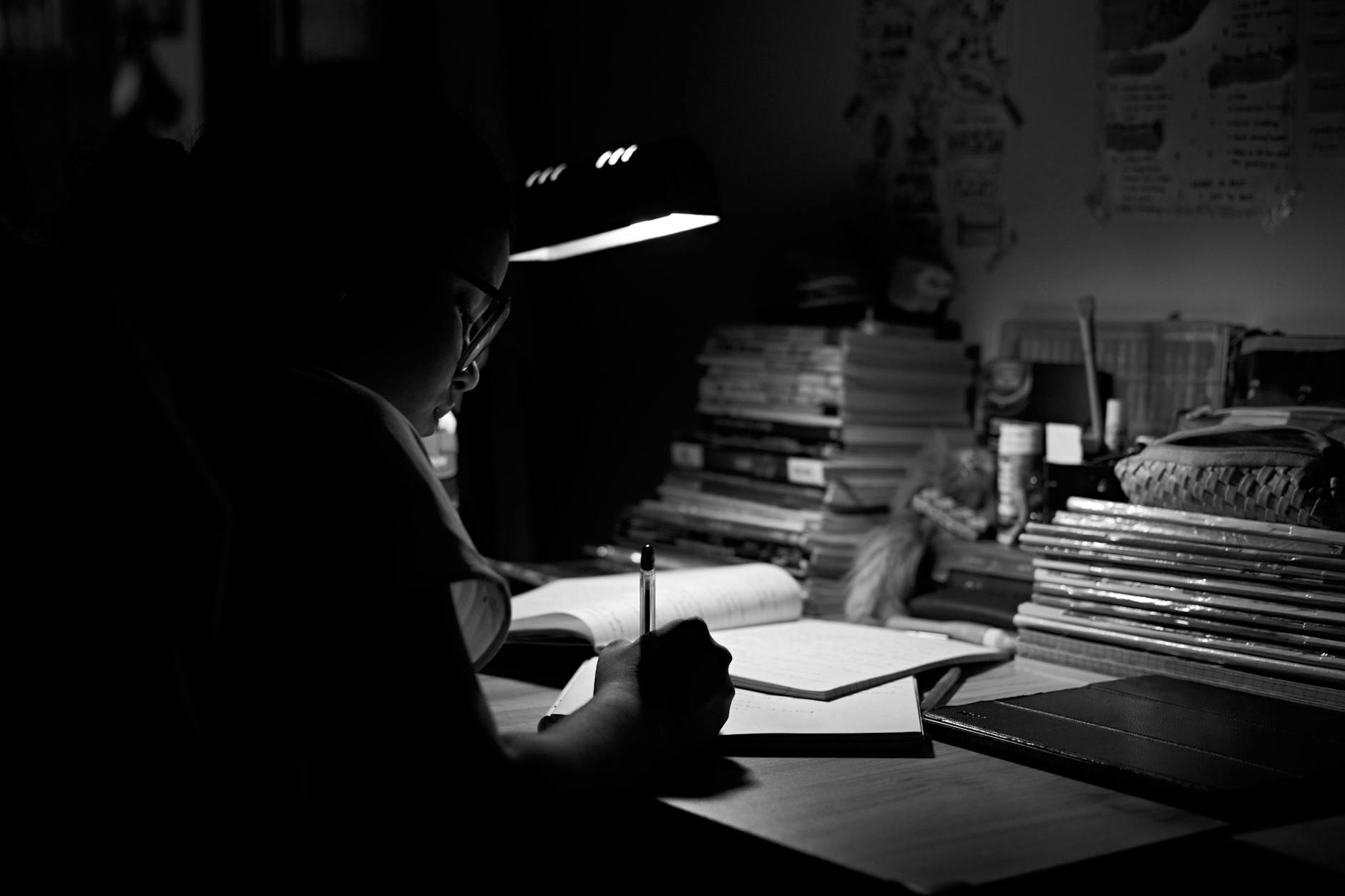

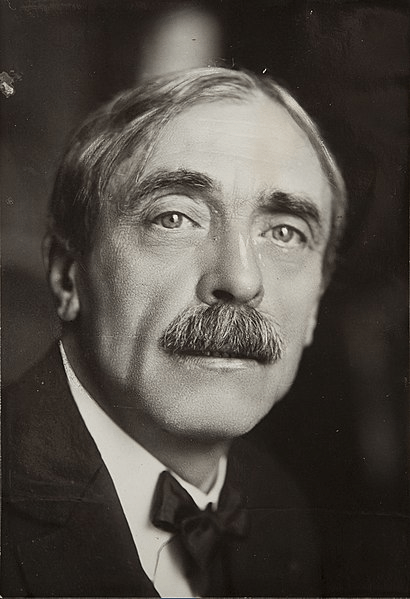

Orson Welles spent most of his career scrapping for money, fighting with producers, and generally trying to balance fifteen spinning plates while doing a magic card trick at the same time. It was an exhausting way to make art.

Still, when indie filmmaker Henry Jaglom was complaining to him one time about not having the time or money to finish a movie the way he wanted, Welles had a tart response:

The enemy of art is the absence of limitations.

This doesn’t mean you should intentionally impoverish yourself to invent challenges. But Welles has a point in that a piece of work can benefit from the creator having something to push against. Set yourself some difficult parameters (it must be this long, I must finish it by this date, if I don’t sell it by this point then I will move on to something else, etc.). The discipline required in overcoming even minor obstacles can give you practice in overcoming the challenges presented by your writing.

Don’t get too comfortable, in other words. Push yourself.

You must be logged in to post a comment.