From William S. Burroughs’ “A Thanksgiving Prayer”:

Thanks for the last and greatest betrayal

of the last and greatest of human dreams.

A film of his reading the full piece, from Gus Van Sant:

From William S. Burroughs’ “A Thanksgiving Prayer”:

Thanks for the last and greatest betrayal

of the last and greatest of human dreams.

A film of his reading the full piece, from Gus Van Sant:

Via A.M. Homes’ introduction to Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery:

When reading Jackson, I can’t help but think of the stories of Raymond Carver, who had a similar ability to create a sort of melancholy emotional mist that floats over his stories. But Jackson also had the ability to be savagely funny: at one point in her career, Desi Arnaz reportedly inquired about her interest in writing a screenplay for Lucille Ball…

Somehow this is actually true. Jackson’s son confirmed it to Michael Schulman at the New Yorker, who couldn’t help noting:

Jackson declined, but one imagines a vial of poisoned Vitameatavegamin…

A world where this had come to pass would be a better one for it.

Fiddler on the Roof premiered on Broadway in 1964, proving that an nontraditional musical about an Eastern European shtetl family being wrenched apart by the struggle over tradition and fears of the next pogrom could play to massive audiences. It still does today.

Last year marked the 50th anniversary of its first production in Japan. Since then it has become that country’s most popular American musical.

Joseph Stein, who wrote the book for Fiddler—stitching together the musical’s characters and themes from the work of Sholem Aleichem—remembered bringing the show to Japan in 1967. He had this incredible exchange about the universality of some works of art:

Japan was the first non-English production and I was very nervous about how it would be received in a completely foreign environment. I got there just during the rehearsal period and the Japanese producer asked me, “Do they understand this show in America?” And I said, “Yes, of course, we wrote it for America. Why do you ask?” And he said, “Because it’s so Japanese”…

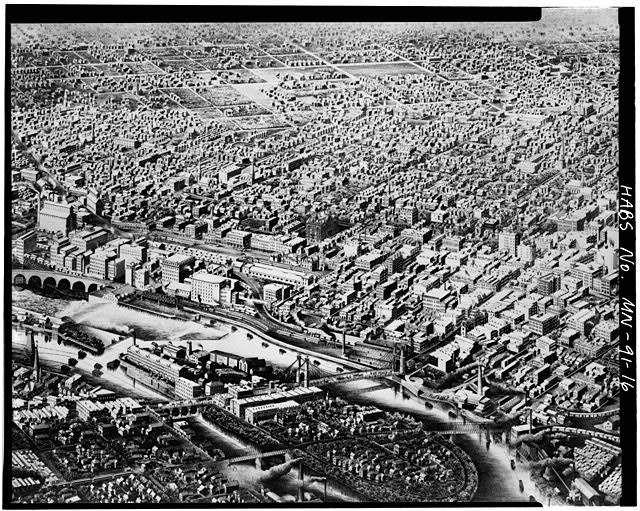

In David Montgomery’s great CityLab article, he tries to delineate the boundaries of that fungible region known as the Midwest. In response to a survey, he finds broad agreement:

…there is a core area that most everyone agrees is Midwestern, including cities like Chicago, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, Omaha, Indianapolis, Detroit, Cleveland, Columbus, St. Louis, and Kansas City.

But things get complicated when you start talking about the “fuzzy boundary regions”:

…places where people are more divided about their alleged Midwesternness. This includes cities like Pittsburgh and Buffalo, New York, where respondents were torn between Midwest and East Coast allegiance; cities like Louisville and Oklahoma City, where Midwestern and Southern or Southwestern identities are in conflict; and places like Rapid City, South Dakota, where the Midwest becomes the West.

Buffalo might not be the East Coast, but Midwest seems a stretch.

Next Monday and Tuesday, Amazon is having its annual Prime Day sale (shouldn’t that be Prime Days?).

For many, this provides an opportunity to load up on all the consumer goods they want and don’t need (100″ TV, voice-operated device that records everything you say and sends it back to Amazon’s server farms for future use by…?). For others it’s an understandably good time to save a few well-needed dollars buying essentials they actually need (diapers, clothes for the kids, food).

But of course, it’s not so simple as a great deal. John Oliver recently broke down what it’s like to work at an Amazon warehouse, where things get particularly Dickensian during the run-up to Prime Day(s):

And now some workers at Amazon’s facility in Shakopee, Minnesota are planning a strike to protest working conditions.

Over at Moby Lives, Ryan Harrington—who noted that some white-collar Amazon workers are flying to Shakopee to join the strike—used the situation to make a helpful suggestion for what to do come Prime Day: Maybe shop somewhere else that day(s).

That applies particularly to books. The American Booksellers Association noted a number of things that your local indie store provides that Amazon, whatever your feelings about them, simply cannot (union labor, drag queen storytime, a cute place to get engaged).

One thing not on their list that absolutely should be: Bookstore cats.

A little late for May Day, but still worth reading. This New Statesman piece looks at the rise of non-utopian socialists who redefine the fight as more of a struggle to simply help people survive the time-sucking grind of modern capitalism. Per Freud: “converting hysterical misery into ordinary unhappiness.”

From Jacobin founder Bhaskar Sunkara:

Imagine ordinary people, with ordinary abilities, having time after their 28-hour work week to explore whatever interests or hobbies strike their fancy (or simply enjoy their right to be bored). The deluge of bad poetry, strange philosophical blog posts, and terrible abstract art will be a sure sign of progress…

From Anthony Lane’s despairing review of the biopic Tolkien:

Why do people keep making films about writers? And why do people watch them? It’s not as if writers do anything of interest. Unless you’re Byron or Stendhal, a successful day is one in which you don’t fall asleep with your head on the space bar. An honest film about a writer would be an inaction-packed six-hour trudge, a one-person epic of mooch and mumblecore, the highlights being an overflowing bath, the reheating of cold coffee, and a pageant of aimless curses that are melted into air, into thin air…

Last month in the Los Angeles Times, Henry Rollins published a beautiful appreciation of Jon Savage’s brilliant new oral history of Joy Division: This Searing Light, the Sun and Everything Else. He included this description of the band’s music, which sums it up better than just about anyone else ever has:

Joy Division’s music doesn’t “rock” in the classic sense as much as shudder, roar and convulse. The songs are readings of temperature, light and lack of light. They walk silently for hours on city streets and return alone to small rooms with full ashtrays and no messages on the machine. It’s a fantastically difficult question to answer: Why do you like Joy Division? The more dedicated the listener, the more likely you’ll get an inhaled breath held for a few seconds, an exhale and a shrug…

Now go listen to Closer about 10 times and you will see what Hank means.

In March of this year, Twitter had an all-hands meeting at which an employee asked why the company can’t do as good a job of keeping white supremacist material off the site as they have done with ISIS propaganda?

According to Motherboard, another employee provided a simple explanation:

With every sort of content filter, there is a tradeoff, he explained. When a platform aggressively enforces against ISIS content, for instance, it can also flag innocent accounts as well, such as Arabic language broadcasters. Society, in general, accepts the benefit of banning ISIS for inconveniencing some others, he said…

The employee argued that, on a technical level, content from Republican politicians could get swept up by algorithms aggressively removing white supremacist material. Banning politicians wouldn’t be accepted by society as a trade-off for flagging all of the white supremacist propaganda, he argued…

A so-called “Ethics in Journalism” bill introduced in the Georgia state legislature proposes the creation of a board that would establish a “canon” of journalism ethics and sanction any journalists who broke them.

According to the Columbia Journalism Review:

The bill would also grant interview subjects the right to request any photographs, audio, and video recordings taken by a journalist, free of charge and at any time in the reporting process. Reporters that fail to respond in a timely manner would face civil penalties.

What kind of penalties?

While the bill would compel journalists to turn over records to interview subjects freely and for free, Georgia’s legislature is exempt from the state’s Open Records Act. Those state agencies that must comply with record requests can charge fees to access public documents, and response times for such requests can run longer than the three days afforded to journalists under Welch’s bill. Once those three days elapse, the bill stipulates, journalists would be penalized $100 per day.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution noted:

The measure was sponsored by Rep. Andy Welch, R-McDonough, a lawyer who has expressed frustration with what he saw as bias from a TV reporter who asked him questions about legislation recently…

As a riposte to all the post-Mueller hand-wringing about “the media” (some justified, most not a bit), Steve Coll provides in the current New Yorker a handy reminder of what it is that journalists do all day and how it impacts real life:

The Washington Post‘s Ann Hornaday has just addressed an obvious lacuna in movie criticism by declaring first that not only has the Great Movie Canon remained stubbornly fixed for too long (Vertigo, Citizen Kane) but that there are many movies post-2000 that stand up alongside all the greats of yesteryear.

Hornaday’s article “The New Canon” is an absolute must-read. She also selected a fairly unassailable list, excepting maybe Spike Lee’s adventurous but uneven 25th Hour and Kenneth Lonergan’s solid but somewhat unremarkable You Can Count on Me. Her list is here but it’s best reading her arguments are each of them as well:

As part of the Brooklyn Museum’s blockbuster exhibition “David Bowie is,” an entire New York subway station has been Bowie-fied.

One element of the takeover is special Bowie-branded MetroCards. This was announced by the transit authority, which gloriously tweeted “Rail Control to Major Tom”:

In Edward McCleland’s book How to Speak Midwestern, there’s a lot to learn about the intricacies and subdivisions of the American Midwestern accent. Take this article, which McCleland adapted from the book, on the history of how the folks in St. Louis speak:

In 1904, the year it hosted the World’s Fair and the Olympics, St. Louis was the nation’s fourth-largest city, behind New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago. It was a center of brewing, milling, and meat packing, and a magnet for Irish and Italian immigrants. That gave St. Louis, and its dialect, a more urban character than most other Midland cities. For example, older St. Louisans still say “youse” and substitute ‘d’ for ‘th.’

That urban characteristic affects not just the vocals of (older, at least) St. Louisans, but everyone’s attitudes:

St. Louis feels more connected to Chicago than it does to the rest of Missouri, which it regards as a hillbilly backwater. A St. Louisan is far more likely to visit Chicago than Kansas City—or Branson, for Pete’s sake.

You must be logged in to post a comment.